Hot glue, ravens and vulnerability – advanced ceramics demands more than a pottery wheel

May 20, 2022

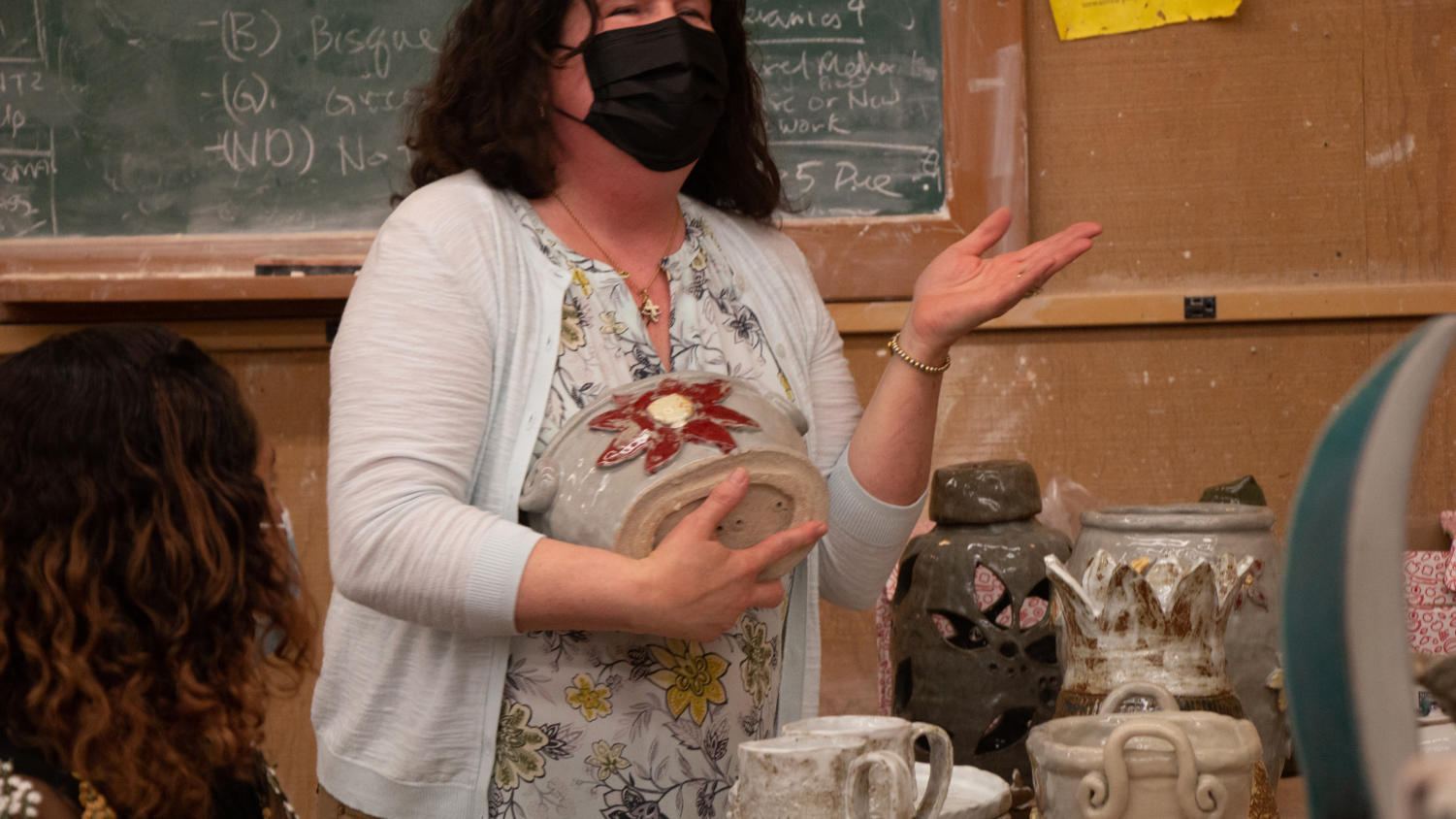

Editor’s note: The following is a photo story covering a session of Ceramics IV as the students present their creations and explain them to the class. A few would go on to be exhibited at the Kruglak Gallery.

Professor Yoshimi Hayashi (right, in the green hat) tells his class that they are advocates for their art. “[I]t can’t talk for you, so if you do it half-ass, you’re advocating for it to be half-ass. Right? So if you’re giving it 200%, then that’s what you’re advocating for,” Hayashi said.

During their critiques, the students of Ceramics IV certainly seemed to have heeded this advice, getting honest and vulnerable as they presented a variety of pieces.

Located in Building 2700 of the MiraCosta Oceanside campus (OC2700), the advanced class meets every Monday and Wednesday afternoon, under the instruction of Professor Hayashi.

Helena Westra walks the class over to her piece, laid on a blanket-like piece of fabric on the ground. “My current body of work is centered around the natural world, specifically the American desert southwest, including Southern California, where I’ve grown to call my home. The work I create is my way of building trust with myself,” Westra says.

“I love clay, because it is simultaneously so freeing, yet it has its own restrictions. Sometimes everything is going well and other times everything gets smashed and crumbles. Sometimes I really feel like I’m fighting it. Other times I have to coax it to get it to cooperate. I like this relationship. There’s a level of problem-solving and compromise required to get the forms I dream of into fireable clay.”

“As for my subject matter, I’m inspired greatly by nature,” Westra added. “When I’m alone in the natural environment out of doors is when I feel most at peace. Everything seems to fall into place exactly where it is meant to be. When I am in nature, I see myself in the world around me. This allows me to feel at home in both my surroundings and in my own body. It is very grounding to be out of doors.”

“I am inspired by the slow and unseen processes of termination, gestation and dormancy – periods of time where large changes are taking place, yet the surface appears so still. This is happening in the buds of flowers and in the seeds of trees and in the kiln that I fire clay in and in the hearts and heads of many humans, including myself.

“Through this body of work, I hope to invite others to share in the exploration of their own growth and to look inwards, to see what might be changing slowly and surely and sometimes outside of the line of sight within them.”

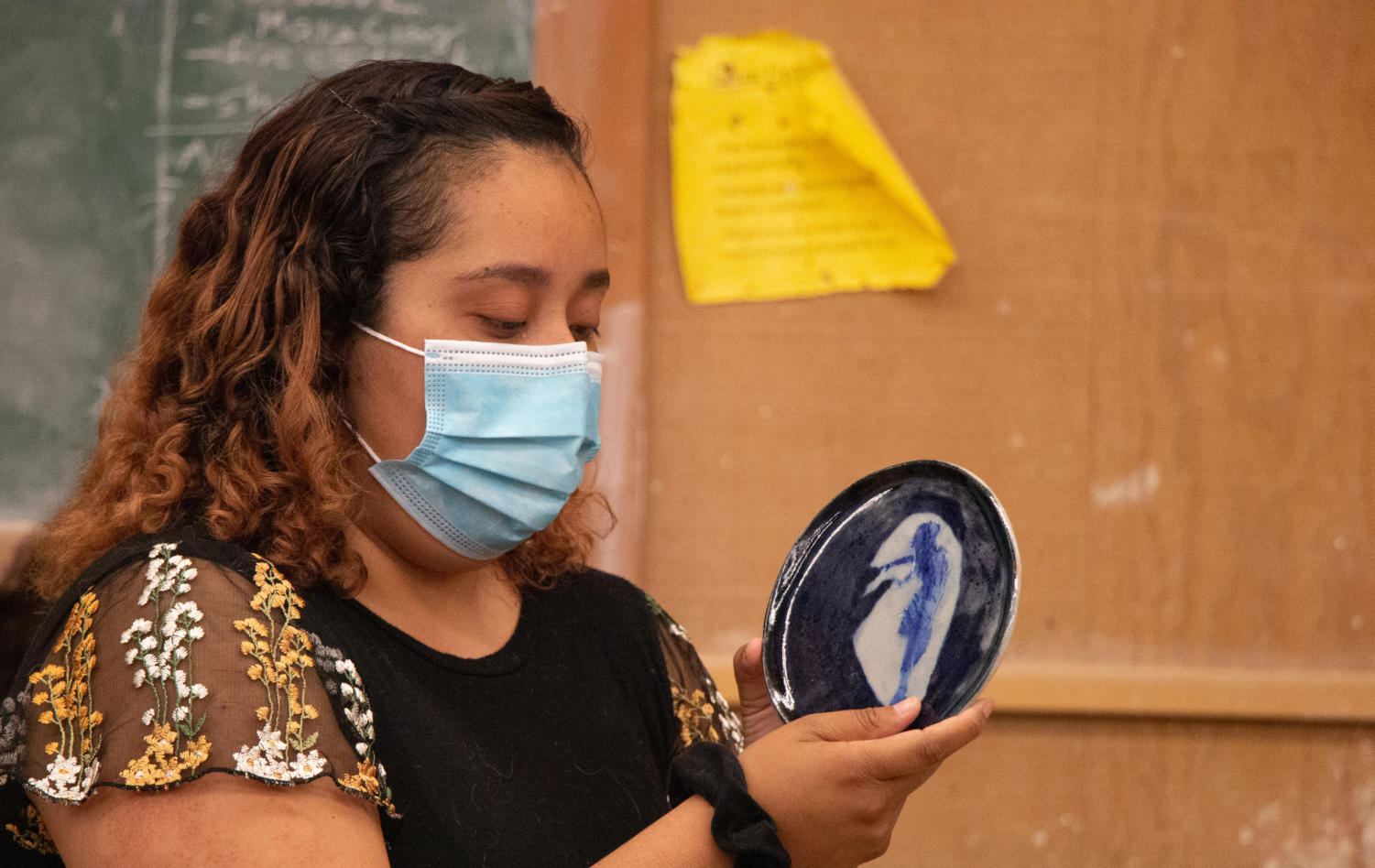

Ponce opens up about using pottery to describe and also navigate her struggles with mental illness. “So I made pieces on my PTSD and it’s been really bad these last couple weeks. I like pottery…, because it’s very controlling and [because of] my PTSD I have control issues,” Ponce said. “For sculpture, it’s the opposite for me because I’ve had sculpture pieces that just fall apart on me [and] it just kind of like, helps me get out of my comfort zone.”

“[Making] these pieces… actually helped me a lot even though I was having really bad six weeks. It helped me a lot because it helped me concentrate on the little things,” Ponce said.

Delos addressed Professor Hayashi during his critique. “When you were saying, like ‘hey, make a mixed medium,’ I initially thought, I’m going to [be] using hot glue for this piece,” Delos said. “Basically I wanted to go back to my older style, of just these organic sketches. And simply, I like to incorporate that- there’s like the organic, disgusting effect that you can get with super glue.”

“I call this ‘The Infection.’ It’s supposed to be – basically, an organism already infected, assimilating another organism. Yeah, it’s supposed byline [is]: ‘bio violating.’ I just wanted to go as disgusting as possible. I wanted it disgusting… and make the viewers just say ‘what the hell is going on?’”

Skidmore’s work follows a theme. “So I was drawn to the raven – I wanted something with a raven and the idea of combining a raven with a cracked pot came up and I wasn’t sure why, so I started researching where the term “crackpot” came from. And there’s actually a little village in Britain called Crackpot, which derives from the Norse word “kraka” meaning crow and “pot” meaning a deep hole or pit,” Skidmore said.

“Crackpot means ‘the hole where crows gather.’ So i’m intrigued that I somehow intuitively connected that the crow and cracked pot could go together. I wanted to be exploring how the two forms would relate in sculpture.”

“So the pots – there’s a smaller version where the raven is gonna be perching on the pot – the cracked pot – and then the larger version of that which I’ll show you in a second, the raven is actually gonna be inside the pot and the pot is gonna be breaking apart away from it.”

“So I was really proud when I stayed after school and stayed til late – late as I could at night working on my big pot.

“Anyway, now so I feel like I’m gradually… the shell around me that’s keeping me from just really full going in my art, it’s starting to crack.”